Main aim of the study

This study aims at understanding how the alignment between the motivational factors of CS participants and the recruitment speech used in the projects’ description is, by performing quantitative triangulation of data collected through a survey about 12 motivational factors for participating in a CS project, and the manual analysis of the projects’ descriptions available in Zooniverse website.

Period addressed by the study

Although the study started at the beginning of 2022 the data needed for the analysis was collected in different periods of time:

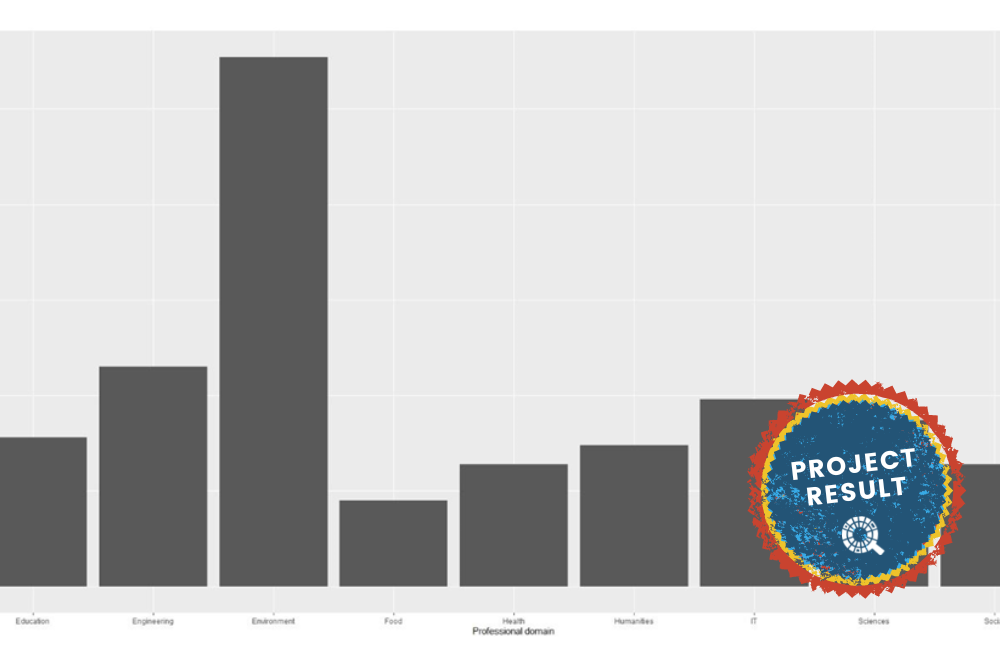

- The CS projects’ descriptions from Zooniverse were extracted in November 2021. A total of 367 projects were available on the platform at that time.

- The questionnaire data were collected over a period of seven months (January-July 2021).

Research question

How well do motivational arguments in project recruitment match the motivational structure of citizen science participants?

Research Context

Since citizen science projects rely on voluntary participants, it is relevant what motivates people to engage in those projects. Most research literature before takes only participation in one specific citizen science project or a specific science field into account. Therefore, we analyse how important motivational factors among self-related and social-related gratifications (Nov et al., 2010) for citizen science volunteers in general. In addition, previous studies rarely considered that citizen science participation underlies also recruitment communication managed by project organisers, despite its importance for successful work with volunteers (Shields, 2009).

Previous literature shows a variety of 12 different motivational factors for citizen science participation like topic interest, social recognition, or contribution to scientific research, connected to different project topics or features (Lampi et al., 2020). These factors, in turn, can be attributed to more large-grained motivational categories regarding more social-oriented arguments like altruistic contribution, joining a community, or social interaction, as well as more self-oriented arguments like enjoyment or project reputation (Lee et al., 2018; Nov et al., 2011).

Research Method applied

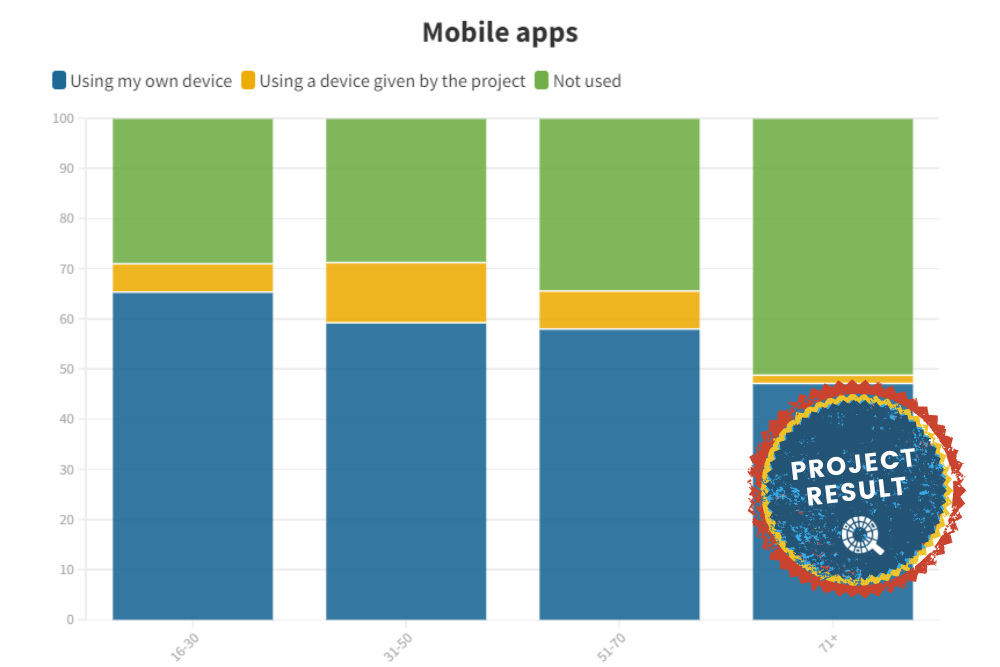

Data has been collected by quantitative triangulation. 1076 participants in citizen science projects answered a survey about the 12 motivational factors for participating.

They had access to the survey through social media posts or email invitations sent to people in charge of projects. Data regarding motivational arguments in recruitment come from quantitative content analysis of 367 project descriptions of the website Zooniverse.

Procedures applied

The procedure applied to perform the quantitative triangulation analysis is presented in the figure below.

Figure 1. Procedure applied in the study.

The manual content analysis of the project descriptions was done by two coders independently. Then, both coders analysed their codings and reached a consensus.

The five coding categories are the desire of contributing (The description asks for volunteer’s help), joining a community (The description invites joining the project/community), social interaction (The description mentions the possibility of socially interacting with other volunteers, experts, etc.), enjoyment (The description appeals to the enjoyment of the tasks to be performed), and project reputation (The description presents details on the name of entities who contribute/participate/fund the scientific research).

Data about the motivational factors for participating in CS projects was collected through 12 likert-scale items. By analysing the definition of the 12 motivational factors used in the survey, 5 were matched with the more general factors used in the descriptions’ coding phase (table 1).

| Coding category | Survey Item |

| Desire of contributing | Desire to help |

| Joining a community | Meeting new people and engaging in a community |

| Social interaction | Opportunities to share existing knowledge with others |

| Enjoyment | Fun and enjoyment |

| Reputation | Social reasons or recognition |

Table 1. Matching between appealing motivations and motivational aspects.

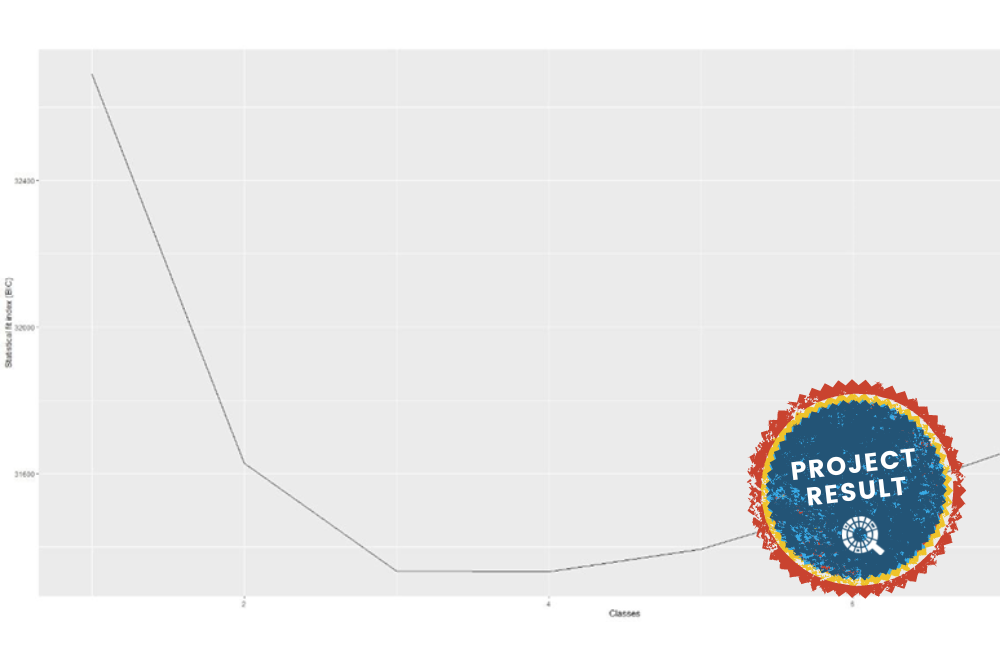

To triangulate data, we first filtered out the answers provided by participants in Zooniverse projects (N=17). By analysing the answers of the Zooniverse sample against the total number of responses, it was determined that they are similar, hence, the total number of survey answers (N=1074) were used for the triangulation analysis. We performed a Binomial GLM test to determine differences between the factors in the projects’ descriptions, while Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to determine differences between the motivational factors of the survey respondents.

Summary of results/findings

Results show that participants mainly take part in citizen science projects because of collective motives, enjoyment and a need for knowledge gain. Analogously, enjoyment and collective ideals are also substantial arguments in citizen science project descriptions. Triangulation of both data might indicate that organisers meet volunteers’ motivations in general, except for the case of social interaction/sharing opportunities, which interestingly is one of the most important motivations for CS volunteers to participate, while it is rarely mentioned in the projects’ descriptions.

Conclusion

Even though our study considered different populations for the motivational aspects of the participants (it included participants of CS projects different from those hosted in Zooniverse) and the content analysis of the projects’ description was limited to Zooniverse projects, our results provide a first insight of how the project organisers understand and align their projects to target engaged participants. Furthermore, the study may suggest a strategy for a wider study that includes CS projects’ descriptions from other platforms and sources. It can also help to generate policy & funding guidelines for pursuing constructive motivations in CS projects.

Link to complete report

Kai Nils, W., Gutiérrez Páez,N.F., Sabel, O. and Hämäläinen, R. (2022) “Is It a Match? Motivations on Citizen Science Volunteers and Recruitment. Arguments in Project Descriptions.” In Proceedings of the ECSA2022 conference: Citizen Science for Planetary Health, 69–70. https://2022.ecsa-conference.eu/files/ecsa/Bilder/ECSA2022_Conference_Proceedings.pdf

Link to dataset

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7310080

References

Lampi, E., Lämsä, J., & Hämäläinen, R. (2020). D4.1: Towards understanding the forms of participation and knowledge-building activities in citizen science projects.

Lee, T. K., Crowston, K., Harandi, M., Østerlund, C., & Miller, G. (2018). Appealing to different motivations in a message to recruit citizen scientists: Results of a field experiment. Journal of Science Communication, 17(1), A02. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.17010202

Nov, O., Anderson, D., & Arazy. O. (2010). Volunteer computing: A model of the factors determining contribution to community-based scientific research. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, 741 – 750. https://doi.org/10.1145/1772690.1772766

Nov, O., Arazy, O., & Anderson, D. (2011). Technology-mediated citizen science participation: A motivational model. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 5(1), 249 – 256.

Shields, P. O. (2009). Young adult volunteers: Recruitment appeals and other marketing considerations. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 21(2), 139 – 159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495140802528658

Photo by Tolga Ulkan on Unsplash