Short summary

Biodiversity citizen science projects investigate, for example, which species of plants or animals exist in an area and how many individuals of each species live in that area. Such projects involve citizen scientists in identifying and monitoring biological diversity and collecting biodiversity data. With the help of citizen scientists, researchers can collect large amounts of such data that they would not be able to collect on their own. We wanted to know how citizen scientists benefit from their participation in biodiversity citizen science projects.

Applied method

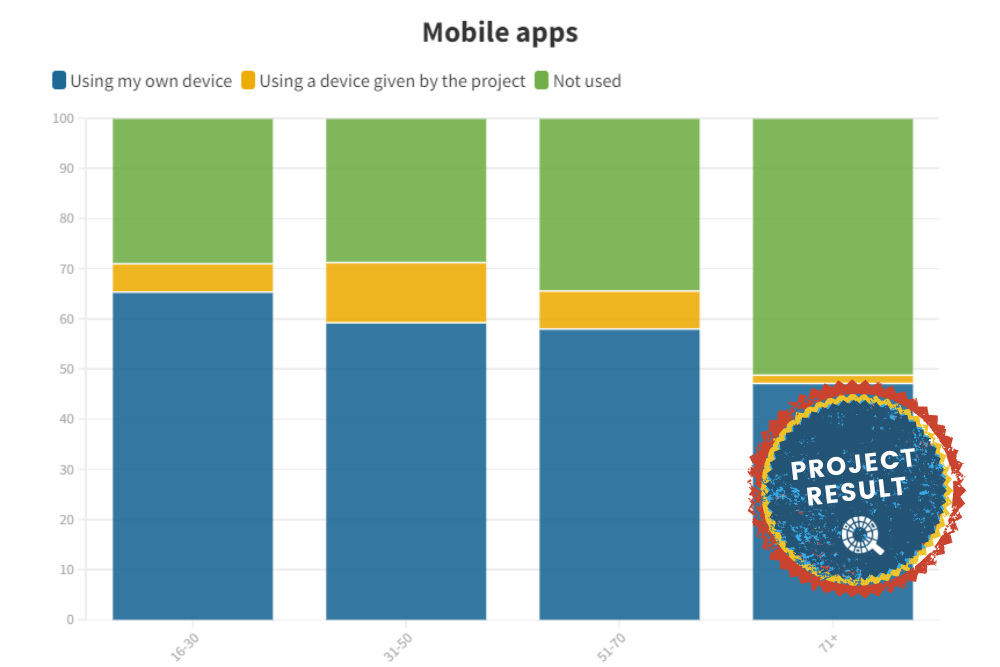

We conducted an online survey and asked more than 1100 participants of biodiversity citizen science projects about their experience. The participants came from 63 projects in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. We surveyed adults who participated in citizen science projects as volunteers. The online questionnaire contained mostly multiple choice questions. In addition, respondents had the opportunity to provide further comments to describe their experience in their own words. We based our study on the framework for citizen science learning outcomes developed by Tina Phillips and colleagues at Cornell University. The framework describes six individual participant outcomes concerning knowledge, skills, self-efficacy, interest, motivation, and behaviour.

Results

Reported benefits.

The reported benefits were greatest with respect to the environment (e.g. knowledge about the environment) and less pronounced with respect to science (e.g. knowledge about science).

Reported gains in data collection skills were higher than gains in skills not directly connected to data collection, such as skills in data analysis, interpretation, and communication.

Behavioural changes mostly concerned communication activities, and to a lesser degree gardening activities and general environmental behaviour.

In addition to the six categories, respondents mentioned a range of other personal benefits, such as health and wellbeing, enjoyment, a sense of satisfaction and contribution, and an increased connection to people and nature.

Conclusion

Our study showed that citizen scientists clearly benefit from their participation in biodiversity citizen science projects.

We therefore conclude that biodiversity citizen science projects have great potential for environmental education. Our study took place in an informal education setting addressing adults. However, citizen science might also be a good way for children and youth in both informal and formal education to experience nature, gain knowledge about different species, and develop an interest in biodiversity.

At the same time, citizen science projects seem to have a somewhat lower potential for science education. Improved project design (e.g. further training opportunities for participants) could make projects more effective in teaching, for example, scientific knowledge and skills beyond data collection.

If we want to find out how to design and develop citizen science projects in such a way that they offer the maximum benefits to both scientists and citizens, more research is needed. Future research could include surveys of both project participants and project staff in order to compare the perspectives of both.

Limitation

We asked project participants about their experience. That means that our study results refer to benefits as perceived and reported by the participants themselves. In addition to evaluating such self-reported participant outcomes it would be useful to objectively measure and assess outcomes. Ideally, such assessment should take place both before and after participation in the project to be able to compare pre- and post-participation responses. However, this kind of study design is difficult to implement in citizen science projects that depend on voluntary participation. Future research would benefit from innovative methods that could measure participant outcomes more objectively, but without deterring participants.

Source

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10193

Photo by Quentin Pelletier on Pexels.