Short summary / Abstract

Most of the project descriptions we analysed focus strongly on science-related learning dimensions while disregarding other personal or interpersonal benefits (such as self-efficacy, attitude or behavioural changes etc).

Only 42 of the 94 project descriptions in our sample contain information on training and didactic materials offered to participants. No more than 6 of them mention interactive training formats.

Introduction

While the main objective of citizen science (CS) projects is generally to answer a scientific question, they might also have many important educational benefits for participants (Bonney et al., 2016; Turrini et al., 2018). In fact, previous studies show that the wish to acquire new skills and knowledge is one of the main reasons for people to join CS projects (Vasiliades et al., 2021; Ganzevoort & van den Born, 2021). Since learning opportunities are an important motivational factor for participation in CS, and project descriptions posted on web platforms play a key role in attracting volunteers, we decided to examine what these texts can tell us about the educational potential of CS projects.

Method

We conducted a qualitative content analysis of a random sample of 94 English-language CS project descriptions stored in the CS Track database, identifying segments in the text that imply learning may take place through participation in that project.

As a theoretical and methodological starting point for our study we chose the widely used and referenced “Framework for articulating and measuring individual learning outcomes from participation in citizen science” developed in 2018 by Tina Phillips and colleagues (Phillips et al., 2018). Building on the six categories of learning outcomes in CS they proposed (Interest; Self-Efficacy; Motivation; Content, Process and Nature of Science Knowledge; Skills of Science Inquiry; and Behaviour and Stewardship), we conducted a qualitative content analysis by manually assigning phrases, sentences and short paragraphs to these categories (and their subcategories).

During this process, new categories emerged because some of the material within our sample did not fit into the original framework. We added one learning dimension—Attitude Change—and two categories related to the deliberate design of learning opportunities for participants—”Training and Didactic Materials provided by the Project” and “Access to Project Results”. At the same time, we chose to exclude the “Motivation” category due to a lack of relevant text in our sample.

Findings

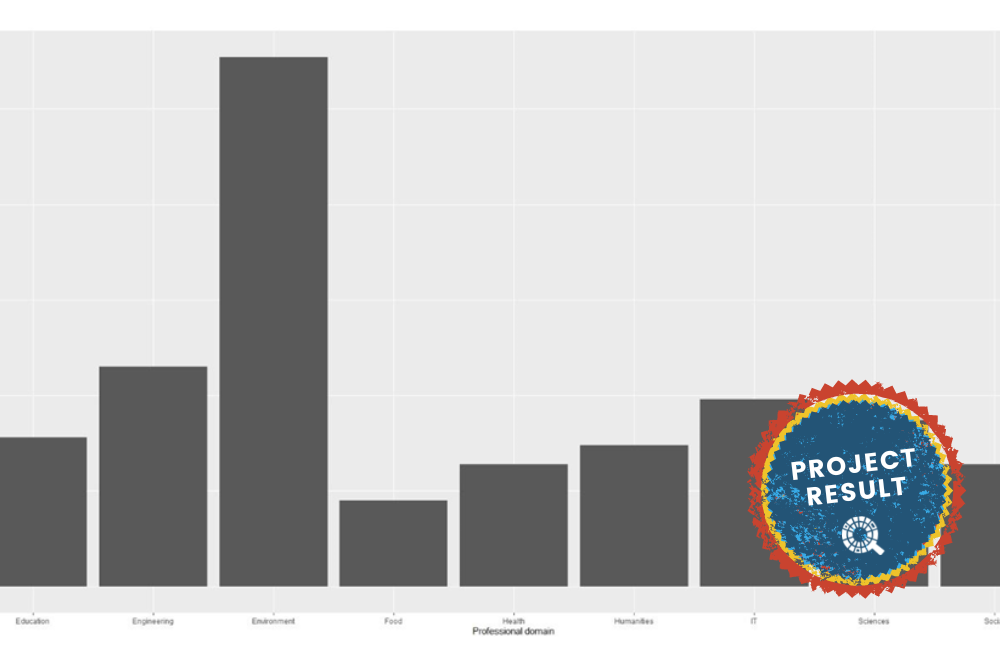

Our results indicate that most project descriptions focus strongly on science-related learning dimensions, such as acquiring new skills and knowledge. Other personal or interpersonal benefits of participation, such as self-efficacy and attitude or behavioural changes, only play a comparatively minor role (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of learning dimensions across main categories.

Within the category of ‘Skills of Science Inquiry’, which was significantly over-represented in the project descriptions we studied, the sub categories data collection and/or submission and using technology were most dominant, with data analysis a distant third (Figure 2.). This result implies that, at least judging from their self-descriptions, most of the projects we analysed do not involve participants in anything relating to study design, synthesis, communication of research results etc.

Figure 2. Distribution of learning dimensions within the ‘Skills of Science Inquiry’ category.

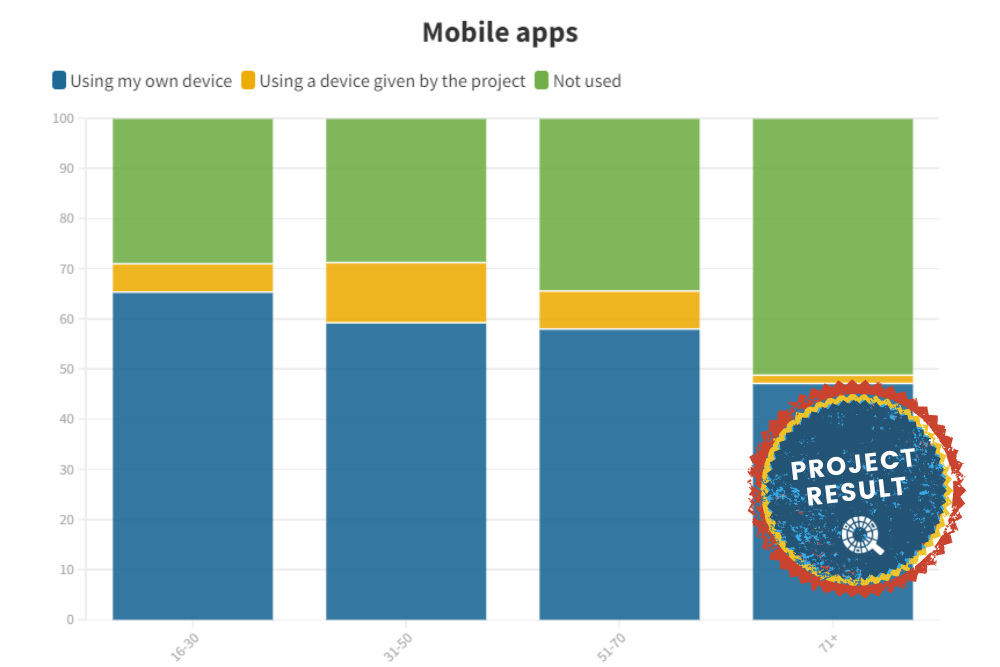

Of 42 project descriptions which contain information on training and didactic materials offered to participants (44.7% of the sample), only 6 mention interactive training formats. This is unfortunate, since recent publications argue that communication and social interaction within the project is key to both learning outcomes and long-term participation (Torres et al., 2022).

Figure 3. Training and didactic materials provided by projects.

Conclusion

Our study revealed a very uneven representation of learning dimensions within CS project descriptions. This result suggests that project initiators and coordinators either do not devote enough attention and resources to creating the broadest possible range of learning opportunities for their volunteers, or do not communicate the educational potential of their project clearly enough in their project descriptions.

The strong focus on science-related learning that we observed seems to be a common tendency in CS, as several publications have pointed out – a tendency that may run counter to volunteers’ actual motivations and expectations (Carson et al., 2021; Roche et al., 2022). It is possible that project initiators and coordinators are not aware of learning dimensions that go beyond science-related topics (such as communication skills, self-efficacy or attitude change). Working with a broader definition of learning – in project descriptions, evaluation practices, and in the deliberate design of learning opportunities for volunteers – could help draw attention to this untapped potential and extend the range of benefits that CS can have on both the individual and the societal level.

Our analysis also revealed that the quality of project descriptions varies considerably and that many do not contain any information on how volunteers will benefit from participating. In light of this observation, we decided to create a set of evidence-based recommendations on how to write effective and engaging CS project descriptions (Golumbic & Oesterheld, 2022), which is available for download from our Zenodo repository.

Limitations

It should be noted that project descriptions do not always provide a comprehensive, detailed picture of what is happening in the respective projects. Moreover, this study was not aimed at capturing how citizen scientists experience the project and what their perceived learning gains are. In order to find answers to these questions, CS Track has conducted an online survey with more than 1000 participants, 610 of whom described themselves as ‘citizen scientists’ (as opposed to project coordinators or professional scientists). The resulting data is now being triangulated with the analysis presented in this paper.

Source

- M. Oesterheld, V. Schmid-Loertzer, M. Calvera-Isabal, I. Amarasinghe, P. Santos, & Y. Golumbic (2022). Identifying learning dimensions in citizen science projects. In proceedings of Engaging Citizen Science Conference 2022, PoS(CitSci2022) 070. [forthcoming]l

References

Bonney, R., Phillips, T. B., Ballard, H. L., & Enck, J. W. (2016). Can citizen science enhance public understanding of science? Public Understanding of Science 25(1): 2-16 [http://doi.org/10.1177/0963662515607406.].

Carson, S., Rock, J. & Smith, J. (2021). Sediments and Seashores – A Case Study of Local Citizen Science Contributing to Student Learning and Environmental Citizenship. Frontiers in Education 6. [http://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.674883].

Ganzevoort, W., & van den Born, R. J. (2021). Counting bees: Learning outcomes from participation in the Dutch national bee survey. Sustainability, 13(9): 4703 [https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094703].

Golumbic & Oesterheld (2022). Writing citizen science project descriptions that spark interest and attract volunteers – a 10-step guide. A CS Track project output. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7004061

Phillips, T., Porticella, N., Constas, M., & Bonney, R. (2018). A Framework for Articulating and Measuring Individual Learning Outcomes from Participation in Citizen Science. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 3(2), 3: 1-19 [http://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.126].

Roche, A. J., Rickard, L. N., Huguenard, K. & Spicer, P. (2022). Who’s Tapped Out and What’s on Tap? Tapping Into Engagement Within a Place-Based Citizen Science Effort. Society & Natural Resources 35(4): 1–17 [http://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2022.2056668].

Torres, A., Bedessem, B., Deguines, N. & Fontaine, C. (2022). Online data sharing with virtual social interactions favor scientific and educational successes in a biodiversity citizen science project. Journal of Responsible Innovation 9(2): 1–19. [http://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2021.2019970].

Turrini, T., Dörler, D., Richter, A., Heigl, F. & Bonn, A. (2018). The threefold potential of environmental citizen science – Generating knowledge, creating learning opportunities and enabling civic participation. Biological Conservation 225: 176–186 [http://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.03.024].

Vasiliades, M. A., Hadjichambis, A. Ch., Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D., Adamou, A & Georgiou, Y. (2021). A Systematic Literature Review on the Participation Aspects of Environmental and Nature-Based Citizen Science Initiatives. Sustainability 13(13): 7457 [http://doi.org/10.3390/su13137457].