Citizen science has, at least in Europe, turned into an umbrella term for a lot of very different practices.

The only thing these have in common is that they involve people in research who come from different professions or different disciplines than those directly relevant to the respective project. Several scholars have tried to solve the problem of defining the term ‘citizen science’ by differentiating between the various forms citizen science can take. In doing so, they have developed categorizations and typologies that are most helpful for theoretical discussion and advancement. However, these categorizations and typologies are too general to assess real-life research projects that engage with the public.

Other scholars do not agree that a typology is even possible (e.g., Prainsack, 2014, Pocock et al., 2019), since any classification scheme can only concentrate on one or a few facets of citizen science while disregarding other, equally important dimensions.

Most existing categorizations and typologies refer to ‘citizen science projects’. This implies a dichotomy between traditional research projects and projects in which lay persons are involved.

After reviewing categorizations in literature, we question this practice of labelling entire projects as ‘citizen science’ or ‘not citizen science’. In reality, such strict distinctions do not hold. Most existing ‘citizen science projects’ do more than involve citizens in science or innovation. Besides, as citizen science contains the term ‘science’, from a linguistic perspective, only those aspects or elements of a project that are related to science can be called citizen science.

Analyzing examples

For instance, when citizens in a project carry out nature conservation activities on the one hand and collect data for analysis on the other, then the project partially qualifies as environment protection and partially as citizen science.

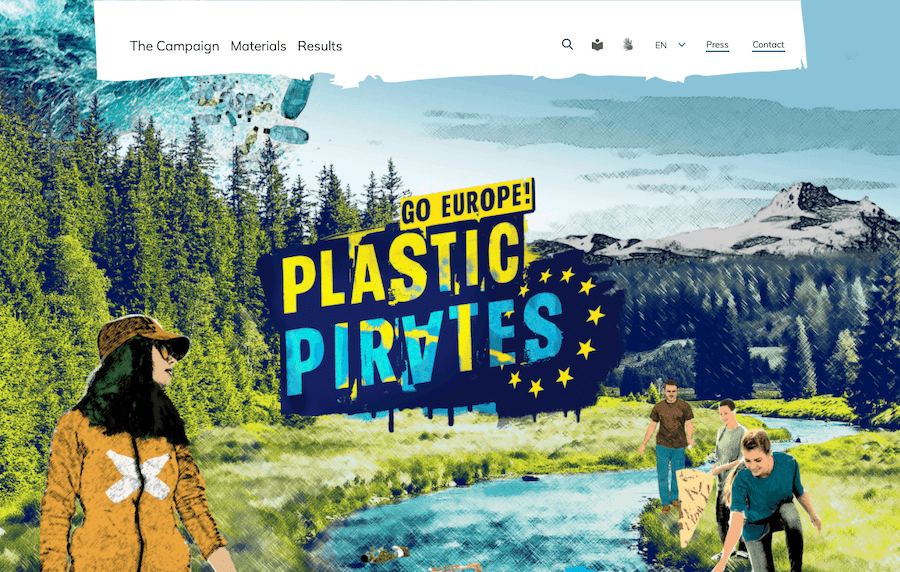

Plastic Pirates is an example of such a project: It combines picking up plastic litter with gathering data. The first activity is not a scientific one per se, hence only the second falls withiin the scope of “citizen science activity”.

Another example is an initiative aiming at improving a community: while much of the project may involve neighbourhood support, the project might also employ citizen science activities to gain knowledge that is important for the project.

Examples of this are citizen initiatives in Japan that, after the Fukushima incident, a nuclear disaster caused by an earthquake and a tsunami, began testing everything – e.g., food, water, soil, grass and dust – for radioactivity because they did not trust the official numbers. With mothers as their main proponents, they developed community services. In one case, they created a medical care centre whose purpose goes beyond dealing with the aftermaths of the nuclear disaster. The main objective is and was not to contribute to scientific research but to safeguard their families and communities (Kenens et al., 2020; Kimura, 2016).

The same is true for a public health project that aims at changing people’s lifestyles and analyzing data on them. Only a part of the project falls into the category of ‘science’ or ‘citizen science’. An initiative pushing for political change and engaging in citizen science to scientifically support their demands does not turn into citizen science as a whole. It remains political activism that also has an element of citizen science. Citizen science very often seems to be one element of a project among others. According to scholars, examples of ‘co-created’ or ‘extreme citizen science’ are rare.

Changing the question

Even if CS is the most prominent characteristic of a project, it will rarely be the only one. Instead of asking if a project is citizen science or not, it might be clearer to ask:

- Which parts of a project are citizen science, and which are something else?

- And which other activities are frequently combined with citizen science?

Additionally, projects can have more than one part that qualifies as “citizen science”, and it may be necessary to evaluate these elements separately, as there are different potential benefits, caveats, barriers, enablers and/or limitations; different guidelines might apply, and best practices could be discussed for each of them.

References

Kenens, J. et al. (2020). Science by, with and for citizens: rethinking ‘citizen science’ after the 2011 Fukushima disaster. Palgrave Communications 6, 58 (2020).

Kimura, A. H. (2016). Radiation Brain Moms and Citizen Scientists: The gender politics of food contamination after Fukushima. Duke University Press.

Pocock, M. J., Tweddle, J. C., Savage, J., Robinson, L. D., & Roy, H. E. (2017). The diversity and evolution of ecological and environmental citizen science. PLoS One, 12(4), e0172579.

Photo by monkeybusiness on Envato elements.