This is a study by the SensJus project.

Short summary

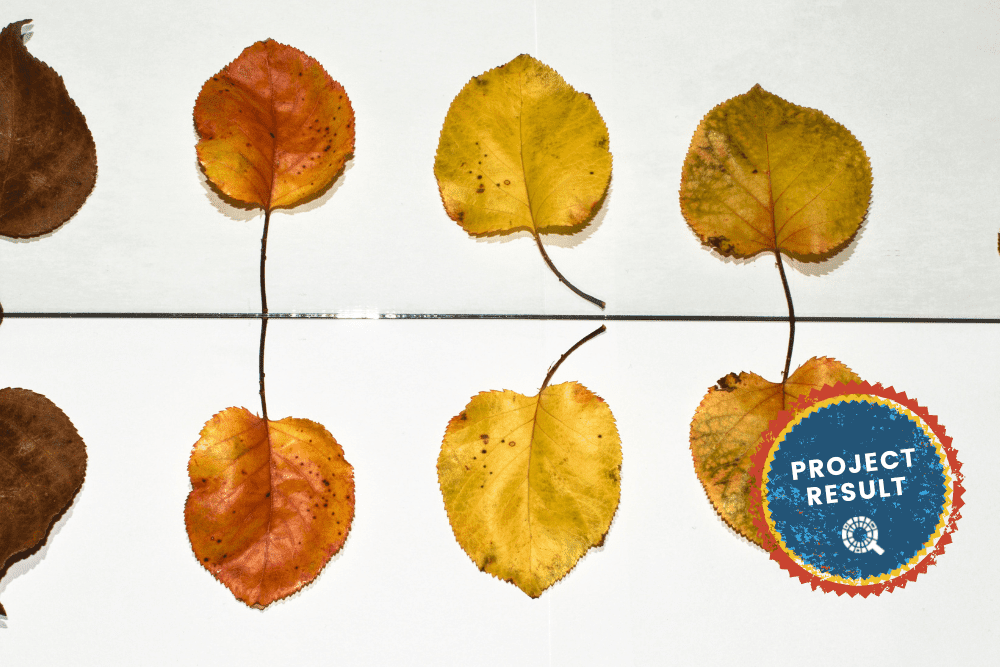

In June 2019, a landmark court decision was issued in Texas, where a judge found a petrochemical company liable for violating the United States Clean Water Act. The case – initiated by a civic group – was mostly built on ‘citizen-collected evidence’ involving volunteer observations of plastic pellets, powder and flakes in the water over a considerable time span. Through a case law analysis of the Formosa ruling, we explore how citizen-collected evidence influenced the judge’s ruling. Although the case has unique features, we identify lessons learned for other citizen-run monitoring initiatives, to strengthen their voice within environmental litigation. We close by suggesting future research avenues, especially in Europe, where the discussion is still in its infancy.

Applied method

We developed a case law analysis focusing on a single case, complemented by a review of literature discussing the use of citizen science in court from both a US and a European perspective. We inspected the Formosa ruling through text analysis, targeting arguments and specific words. We complemented this study with an inquiry into communications that accompanied the ruling, to understand how the case was received by interested communities. Furthermore, we benefited from consulting two US experts. We also discussed our work with a spokesperson for the Formosa case plaintiffs and with one of the plaintiffs’ attorneys, who provided important insights into the ruling and strategy.

Results

This analysis allowed us to respond to our preliminary and key questions, and to extract generalizable lessons also for European citizen scientists, considering however that in Europe we have not yet witnessed a judicial case decided mostly based on citizen-collected environmental evidence. In terms of the types of evidence that count as citizen science in the Formosa litigation, we can say that videos, pictures, and plastics-containing bags (collected by local residents and coordinated by a non-profit organization) represented citizen science data. Interestingly, in response to our question regarding how the judge classified this evidence, we can affirm that the judge did not label any of the provided evidence as citizen science. The judge considered the evidence for its reliability and robustness confronting it with other evidence (e.g. company’s own audits; findings of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality) that was brought to the court’s attention by the plaintiffs. A similar outcome in terms of court assessment could likely occur also in Europe where most national legislations do not recognize civic-collected evidence as a distinctive evidentiary source.

The role played by citizen-collected evidence in the judge’s decision in this case seems complementary; it reinforces other evidence. The judge’s ruling is brief when it comes to reasons for accepting the evidence, possibly in part because the citizens’ evidence was not significantly challenged by the company. The fact that the court did not characterize the evidence as citizen science is not surprising because the term does not have any legal significance. The court just has to determine whether evidence from any source meets the standards of the Federal Rules of Evidence. In European countries, specific procedural law provisions may apply depending on the country in question. To further explore the issue at hand, an analysis of the norms applicable to different forms of citizen science evidence in court would be particularly useful. We deem that such research should be country-specific, considering the changing procedural law scenarios in different countries, yet bear in mind a European comparative lens of analysis.

Conclusions

From the analysis developed, we conclude that, first of all, citizen science can be a useful source of evidence especially when it is able to fill company and government agency’s reporting gaps. From an operational point of view, we can note that the hurdle of presenting citizen-collected evidence is lower where the process of gathering evidence is relatively nontechnical and based on ordinary observations, as opposed to processes using sophisticated techniques and instruments. The more sophisticated the sampling, the greater the likelihood the defendant or the court may challenge the procedure for taking samples.

The Formosa case also illustrates that the criteria courts apply to determine what counts as valid evidence is based on specific subjective, spatial, and material considerations. From a subjective perspective, citizens must demonstrate they are personally affected. Furthermore, from a geographic perspective, the evidence is inherently localized and spatially situated. From a material standpoint, the civic evidence accepted by courts must be tangible or perceptible. The easier the proof of perception, the more likely the evidence is accepted.

As there is no specific set of rules expressly dedicated to citizen science evidence, plaintiffs may be unsure how to proceed. But this can also be encouraging, as the court did not seem to be concerned about who presented the data. However, we can affirm that it would help future cases if judges could provide better guidance on the standards they apply to citizen science. We would welcome a legal recognition at a procedural level of this peculiar category of evidence, especially considering its potential to fill official and private actor’s reporting failures.

The table below illustrates winning strategies that the plaintiffs in the Formosa case adopted, and possible overarching lessons.

Winning ingredients for the admissibility of citizen science data in court.

Although at present there are no examples of judicial cases where environmental damage was prosecuted based on citizen science evidence in Europe, a potential for this type of evidence can be found in climate litigations which are mobilizing critical masses of affected and concerned citizens. With the SensJus project, for example, we are exploring the potential of introducing civic collected evidence of climate distress in the first Italian climate litigation, Giudizio Universale, filed this summer.

Limitations

A first limit of this discussion is its uniqueness to the US legal system, which means that the conclusions drawn here may not hold elsewhere. For example, in the US, plaintiffs can sue a company to enforce permit terms without going through the state or the competent agencies, which is not the case in other countries, for example in Europe. Furthermore, even within the US legal panorama, the case is quite unique, because of the wealth of evidence gathered by plaintiffs and the time-span covered, the total lack of company reporting, the failure of the competent agency, and the high settlement sum. We were also limited by the parties consulted. Whereas we engaged in exchange with plaintiffs, we did not have the same exchange with the company.

References

Berti Suman, A and Schade, S. 2021. The Formosa Case: A Step Forward on the Acceptance of Citizen-Collected Evidence in Environmental Litigation? Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 6(1): 16, pp. 1–13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.367

Would you like to know more?

Youtube recording of a webinar over the study.

In consultation with Amy Johnson, lawyer of the plaintiffs’ of the Formosa case, we would like to stress two points. On the sentence ‘From a subjective perspective, citizens must demonstrate they are personally affected’, we meant that in order to file a lawsuit citizens must demonstrate to have an interest, i.e. legal standing. However, citizens do not need to demonstrate to be personally affected to present evidence. Anyone can present evidence in an American court, without necessarily having an interest.

On the idea of development of standards of admissibility for citizen science evidence in court, again in consultation with Amy Johnson, we acknowledge that such a recognition is not needed in the US where the Federal Rules of Evidence apply (under factual evidence). In Europe, however, as a civil law system, the lack of explicit recognition is not only creating uncertainty but it is also often putting at risk those citizens that gather evidence on the ground (for example close to companies’ premises). In such contexts, a legal recognition may be advisable.

[…] example, a case that inspired us was civic monitoring of plastic pollution in the Lavaca Bay in Texas, run exclusively by local fisherwomen and […]