With citizen science, it is possible to gather and analyse data across environmental, natural and health sciences, humanities and arts, and engage and empower additional people to join the debate about the future.

However, to demonstrate the full potential of citizen science, we must demonstrate its impact and value.

What do we mean by impact?

How has the impact of citizen science projects been assessed previously?

In the MICS project funded under the European Commission’s SwafS programme, we analysed 77 peer-reviewed publications as well as ten past and ongoing citizen science projects to investigate how the impact of these projects is typically assessed.

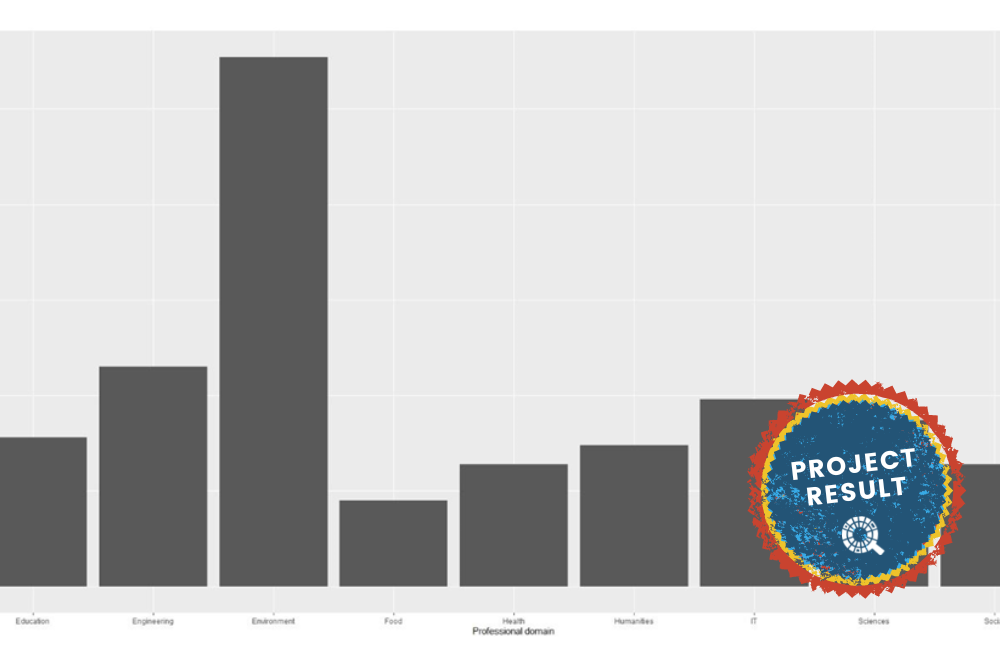

As might be expected, the methods were highly varied. Although nearly all projects used a mix of quantitative and qualitative approaches, most projects only measured impact in one or two categories, with only two out of the 80 reviewed publications referring to all five. ‘Society’ was the most assessed category, whereas ‘Economy’, perhaps unsurprisingly, was rarely investigated. The “depth” of these analyses also varied, with the majority of projects only considering impact at the thematic level (for example, the theme of biodiversity within the category of science), and very few considering impact at the indicator level (more specific measures, such as if the project explicitly informs any governmental policy process, or if the project explicitly fosters new collaborations amongst societal actors and groups).

The CSIA framework

From this review, we have developed a citizen science impact-assessment framework (called CSIA): a set of guiding principles to enhance the ease and consistency with which impacts can be captured. These principles are:

This final principle is essential. In order to remain relevant and serve the citizen-science community, the CSIA needs to be built on evolving intelligence, based on continuously added inputs and definitions by researchers and practitioners.

Finally, these principles and the research described here are related to the overarching goal of the MICS project (Developing metrics and instruments to evaluate citizen-science impacts on the environment and society): to develop an ever-evolving platform for measuring the impact of citizen science projects, and to demonstrate the full potential of this promising field.

The implementation of the framework

To be actionable and sustainable, the CSIA framework needs to be implemented as software, and Alquimics is the algorithm behind the MICS platform, which is being created based on the framework. It is being created through part handcrafting (a labour-intensive technique for programming that involves writing explicit rules and templates) and part machine learning (a type of AI that learns to perform a task by analysing data patterns).

From the start, the team has been facing a defining question: which parts of the platform’s brain should be handcrafted and which should employ machine learning? Handcrafting is the more traditional approach in which scientists painstakingly write extensive sets of rules to guide AI’s understanding and assessments. Statistically-driven machine-learning approaches, by contrast, have the computer teach itself to assess impact by learning from data.

Machine learning is a superior method for tackling so-called classification problems, in which neural networks find unifying patterns in noisy data. However, when it comes to translating indicators characterising citizen science projects into impact assessment, machine learning has a long way to go. As such, the team finds itself struggling, like the tech world at large, to find the best balance between the two approaches.

Handcrafting is unfashionable; machine learning is white-hot. To help Alquimics automatically generate impact assessments, the team will have at its disposal only 10-30 sets of instances of about 300 indicators.

Do you want to test Alquimics and help to refine the framework? Send us a message! (lceccaroni@earthwatch.org.uk)

References

Photo by Mikhail Nilov in Pexels